Joseph Kellogg’s Early Life in Slavery and Freedom, Forsyth County, Georgia

by Mark Auslander

Joseph Kellogg (date unknown)

What may we infer about the early life of Joseph Kellogg (c. 1842-1927), during the time when he was enslaved? Family lore recalls that Joseph and his parents Edmond and Hannah Kellogg were enslaved by George Walker Kellogg (1803-1876). a prominent mine owner, businessman, and sometime George State representative, who resided in Forsyth County, Georgia, from about 1836 onward. It is further that recalled that around the time of emancipation, Joseph Kellogg acquired some land, evidently from his former enslaver.

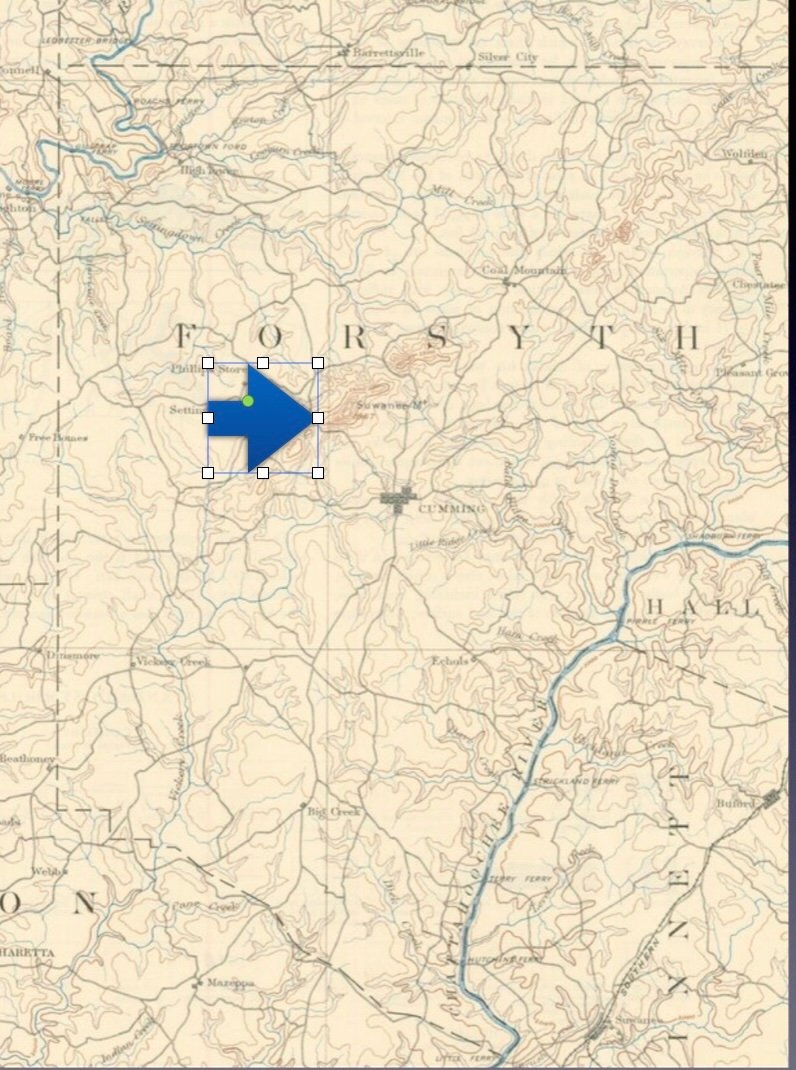

At the time of the horrific 1912 Forsyth County, Georgia racial cleansing, in which about 1,100 Black residents were expelled from the county, Joseph was generally reckoned as the leading Black landowner in the county, owning about 200 acres near Sawnee mountain (about three miles northwest of Cummings, the county seat,( as well as some land lots within he city of Cuming itself.

The 1870 census records Joseph Kellog residing with his parents Edmund and Hannah Kellog, as well as his future wife Eliza Thompson, whom he marred legally the next year. His age is listed as twenty eight, suggesting he was born in 1842, consistent with the age given in the 1880 census. (The 1900 census has him as somewhat older, born in 1834, but the 1870 age listed is presumably more accurate.)

The Enslaver George Walker Kellogg

The enslaver George Walker Kellogg was born in Litchfield, Connecticut and appears to have arrived in Jackson County, Georgia, around 1826, soon after his marriage to Caroline Webster in Connecticut. Their son George Walker Kellogg, Jr was born in Jackson County in 1828. The 1830 census shows George Walker Kellogg in Hall County, adjacent to the Cherokee lands that two years later would become Forsyth County.

The white Kellogg family had moved into Forsyth County by 1835 As early as 8 June 1835 George Kellogg is recorded in County Deeds as purchasing land in the County.. Kellogg was in 1836 appointed as an appraising agent of Cherokee property, determining if tribal land owners had “improved” their land (that is to say installed Western-style agricultural elements) and were thus entitled to compensation, as they were pushed out of northeast Georgia towards Indian Territory (later known as Oklahoma).

How did Kellogg acquire his slaves? Since George Walker Kellogg arrived from the relatively free state of Connecticut this means that Edmond (born in South Carolina) and his wife Hannah Kellog were likely purchased within Georgia, Since the 1830 census indicates that G.W. Kellogg did not yet own slaves, he likely purchased Edmond and Hannah after 1830., in Hall or Forsyth counties. The 1840 census in Forsyth County indicates Kellogg owned ten slaves, among these a male aged 10-23 years, who might have been Edmond (later recorded as born around 1808), and a female, age 10-23, who might have been Hannah, born around 1817.

Slave sales in Georgia were sometimes recorded in Deed books as real estate transaction and sometimes listed in Probate records under public sales held to settle the debts of an estate of a deceased person, often in front of the county courthouse,

Between 1832-1834, Kellogg made around 8 land purchases including mineral interests in Hall County, but no slave purchases by him are recorded in the Hall County Deed books. In turn, a review of the early Forsyth county Deed books from 1835 to 1840 shows Kellogg purchasing at least 25 tracts of land in the county, but no slave purchases are noted.

It thus seems most likely that Kellogg purchased slaves at one or more public sale estate auctions in Hall County between 1832-1834, or in Forsyth County between 1835-1840. Purchasers are normally noted in the left hand column of Estate sale records in Probate records. My preliminary review of Book A (1833-1844) of Miscellaneous Estate Records (Court of the Ordinary) in Forsyth County does not record any slave purchases by George Kellogg, but a more detailed review might be helpful, as would a careful read of the l830-1834 loose probate records for Hall County.

In any event, if Edmund and Hannah’s son Joseph was born around 1842, then it may be that he is the nine year enslaved “mulatto” boy in George Kellogg’s 1850 slave schedule and the 16 year old enslaved young man in George Kellogg’s 1860 slave schedule.

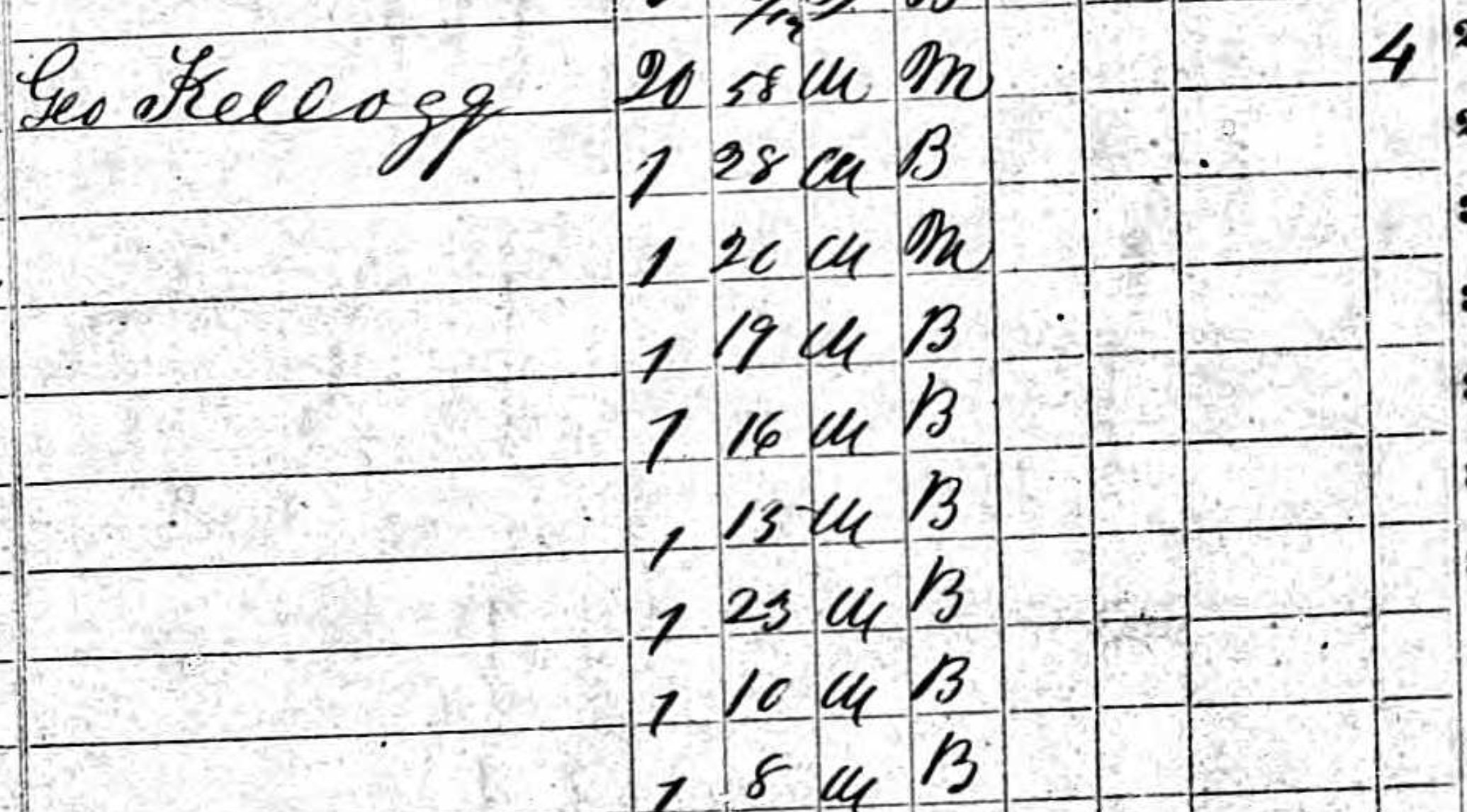

1860 Slave Schedule for George Kellogg (detail). Perhaps the 16 year old male is Joseph Kellogg. The first line indicates that the enslaved resided in four dwellings.

The 1860 slave schedule records that George Walker Kellogg’s slave resided in four slave dwellings. Perhaps one of these housed the family of Edmond and Hannah.

The enslaver George Walker Kellogg owned at least one gold mine in the area, and was one of the leading providers of gold to the US Government mint at Dahlonega, in Lumpkin County, north of Forsyth County. (Indeed, Kellogg served 1860-61 as the final superintendent of the mint, up until he wrote a letter of resignation to President Lincoln, following Georgia’s secession from the Union in January 1861. After this the mint was turned over to the Confederacy.

It is thus possible that young Joseph Kellogg, prior to emancipation in 1865 (when he was about 23 years old) worked in one of George Walker Kellogg’s gold mines. The white George W Kellogg was a ticket agent for local railroads, served as director of at least two rail road companies, and served as postmaster at the settlement of Coal Mountain, so it is possible that enslaved members of the Kellogg family labored in support of these enterprises as well as farming operations and in the Kellogg household.

What was Joseph’s likely religious upbringing? The enslaver George Walker Kellogg and his wife Caroline were converted to Methodism in 1842, Soon after this, George served as as the secretary of the Dahlonega Circuit of the Methodist Episcopal Church. He signed in August 1844 a missive in the Southern Christian Advocate denouncing the recent move by Northern Methodist bishops to expel Bishop James Osgood Andrew from the episcopacy, a controversy that led to the great schism of the Methodist Episcopal Church over the following year. (For a detailed discussion of this schism and the enslaved people owned by Bishop Andrew, see my book The Accidental Slaveowner: Revisiting a Myth of Race and Finding an American Family. Georgia University Press, 2011). Kellogg also played a role in the raising the Methodist Ebenezer Church in Cumming.

Joseph Kellogg’s Youth

t thus seems likely that the enslaved Joseph Kellogg was raised in a Methodist context. Indeed, Joseph is recorded as a founder in 1879 of the Colored Methodist Campground, which was to play a significant role in the tragic events of 1912, when whites absurdly branded a gathering by Black elders there as a prelude to a Black violent mass attack on the county’s white residents.

Family oral history recalls that Joseph’s wife Eliza Thompson, c 1845-1920, escaped from slavery at least twice, including during the late Civil War period. I am not sure of her enslaver and have not yet come across a runaway slave advertisement that appears references her.

The Civil War appears to have bypassed Forsyth County, and it does not appear that any Black Kellogg family members had an opportunity to join the US Army during the conflict. However, a great many white males from the county served in the Confederate military. Among these was Truman Ezra Kellogg, the son of George Walker and Caroline Kellogg, who served in the 14th Georgia Infantry, Co. E, enlisting as a corporal on 4 July 1861 and rising to 2nd Sergeant. He was killed in action in the 2nd Battle of Manassas (Bull Run) on August 29, 1862. A number of prominent Georgians did send enslaved male servants to serve as as manservants for young white male soldiers during the war, but I do not know if this happened in Truman’s case.

Georgia was declared a Federal Military District in June 1865. It is likely that Forsyth County was occupied by US troops around that time, as enslaved persons were informed that the Emancipation Proclamation was now finally in effect, and that they were forever free.

As of this writing, I am not sure how land was acquired by Joseph Kellogg after Emancipation. In the Land Records for Forsyth County, Book N 1860-1867, Book O, 1867-1873, Book P, 1873-1878 (that is to say the records that cover the postwar lifespan of George Walker Kellogg up to his death on 14 May 1876), do not list any land transfers involving Joseph. The 27 May 1871 will of George Walker Kellogg does not make any mention of Joseph or any other person of color. There may have been informal land transfers that were not recorded in the county deed books or probate records.

1894 map

It should be noted that Forsyth County Deed Book R, 1883-1890, does list at least seven land transactions involving Joseph Kellogg, starting with a sale in February 1885 with Hampton Barker, for lot 1088, which indicate that by this point Joseph was a legal property owner.

I hope that future research will cast more light on the early life of Joseph Kellogg, the patriarch of such a remarkable, far-flung family.

For further reading

Jaspin, Elliott. Buried in the Bitter Waters: The Hidden History of Racial Cleansing in America. Basic Books, 2008.

Phillips, Patrick. Blood at the Root: A Racial Cleansing in America. W.W. Norton & Company, 2016.

On line exhibit: Race and Reckoning in Forsyth County

1912-2020

https://georgia-exhibits.galileo.usg.edu/spotlight/forsyth-race-relations/feature/stolen-land